Gary Mark Smith Critical Review 1

Following is the forward essay by James R. Hugunin to G. Mark Smith’s street photography journal Searching For Washington Square, about Smith’s global street photography method. Hugunin teaches photo history and contemporary theory at The School of the Art Institute of Chicago and is Managing Editor of U-Turn E-zine:

*Global Wandering As Method

His interest (Constantin Guys) is the whole world; he wants to know, understand and appreciate everything that happens on the surface of our globe . . . The crowd is his element . . . For the perfect flâneur, for the passionate spectator, it is an immense joy to set up house in the heart of the multitude, amid the ebb and flow of movement, in the midst of the fugitive and the infinite …

— “The Painter of Modern Life,” Charles Baudelaire

In his autobiographical photo-travelogue, Molten Memoirs (1999), Gary Mark Smith confesses that thirty years ago he had “dreams about becoming an artist (it was a contrary world I saw myself heading into) and traveling the world. Or maybe even becoming an artist known for including his wanderlust as a principal notion in his methodology.” Such a method is a time-honored one. In Eastern literature we have the wandering Japanese poet Basho (1644-1694) who, in his Records of a Travel-worn Satchel, wrote: “From this day forth I shall be called a wanderer . . .” Basho’s haiku has the vivid immediacy of a street photographer’s grabshot:

Time and time again, nipped by a sickle, with a click — beautiful, beautiful cherry.

Smith might rewrite this stanza as:

Time and time again, loading my camera, with a click — beautiful, beautiful street.

And there was that literary gadabout Henry Miller, who in his preface to his bittersweet “travelogue” across America, The Air Conditioned Nightmare (1945), said of the typical American home: “It was home, with all the ugly, evil, sinister connotations which the word contains for a restless soul.” Further in that book, Miller could be describing the street photographers’ raw material: “Events transpire in all declensions at once; they are never conjugated.” Never conjugated, that is, until the camera’s click paradoxically suture’s together (as Roland Barthes has noted) “That has been” with “There it is.” Closer to Smith’s time and his Lawrence, Kansas home we find singer Hank Williams (1923-1953), who recorded his atypical music under the alias Luke the Drifter. One of those songs, Pictures From Life’s Other Side (1951), recalls the range of Smith’s bittersweet observations while roving that theater, The Street:

There’s pictures of love and passion, and there’s pictures of peace and strife. There hang pictures of youth and of beauty, of old age and the blushing young bride. They all hang on the wall, but the saddest of all, are the pictures of life’s other side. Just a picture from life’s other side, someone that fell by the way. A life that’s gone out with the tide…

The idea that the world is a stage (Theatrum mundi) has a long tradition. In 1858 a journalist, Victor Fournel, wrote a book titled Ce qu’on voit dans les rues de Paris (What one sees on the streets of Paris); employing the metaphor of the street-as-theater, Fournel declaimed: to stroll the sidewalks was to “take my seat in the pit of this improvised theater.” Gary Mark Smith has taken his place before the global stage of street life; with his camera in hand, he’s become an active bystander of the sorts originally played by the chorus in Greek drama. Smith speaks passionately about his fascination with street life, recalling poet Czeslaw Milosz’s comments after arriving in Paris after World War II: he spoke of his “joyous immersion in the reservoir of universal life . . . a swimmer who trusts himself to the wave, and senses the immensity of the element that surrounds him.” It is this oceanic feeling that Baudelaire attributes to the artist Constantin Guys in The Painter of Modern Life.

“Gary Mark Smith has taken his place before the global stage of street life; with his camera in hand, he’s become an active bystander of the sorts originally played by the chorus in Greek drama.”

German critic Walter Benjamin, in On Some Motifs in Baudelaire (1939), extrapolates from Baudelaire’s insights on the observer of the amorphous crowd to photography and the modern scene: One abrupt movement of the hand [like lighting a match] triggers a process of many steps. . . . Of the countless movements of switching, inserting, pressing, and the like, the “snapping” of the photographer has had the greatest consequences. . . The camera gave the moment a posthumous shock, as it were. . . Moving through this [city] traffic involves the individual in a series of shocks and collisions. . . Baudelaire speaks of the man who plunges into the crowd as into a reservoir of electric energy. Circumscribing the experience of the shock, he calls this man “a kaleidoscope equipped with consciousness.”

“Nearly all these images are sympathetic toward their subjects, foregoing the aggressiveness and social satire of street photographer Garry Winogrand’s oeuvre. Whereas Winogrand remained an outsider on the street, Smith seems to resonate with the energy of the crowd, empathize with his subjects.”

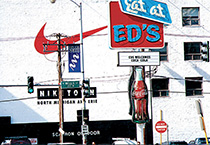

Indeed, Smith’s vision of the global street scene is kaleidoscopic. His book tracing his many journeys is divided into blending sections; the opening segment includes slices of unpopulated streets, formal compositions that startle by the power and oddness of their found juxtapositions as in Eat At Ed’s/Chicago, Illinois which makes a typical Tod Papageorge photograph appear modest by comparison.

Then the complexity of diverse street elements are added, as found in American Skate-Scape/West Lafayette, Indiana …or humorous roadside attractions make their debut like we see in BeerBottle BigScape/ Washington, Pennsylvania.

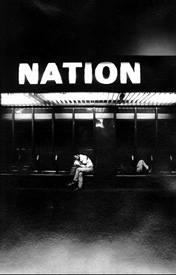

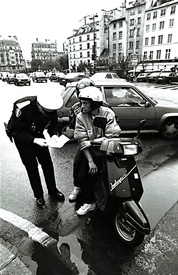

This section is also devoted to street people the world over, as in the very funny image of an sedate old man flanked by outrageously garbed transvestites in Odd Man Out/Toronto, Canada. But not all these street folks stand out due to their oddness; many are ordinary folk playing a musical instrument … catching the sun … reading a newspaper … curiously peering out windows … or just dozing.

Nearly all these images are sympathetic toward their subjects, foregoing the aggressiveness and social satire of street photographer Garry Winogrand’s oeuvre. Whereas Winogrand remained an outsider on the street, Smith seems to resonate with the energy of the crowd, empathize with his subjects.

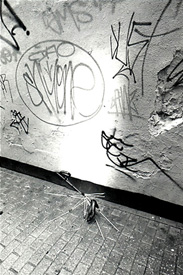

Next follows a brief glimpse at the “bawdy street,” where one figure sports pants emblazoned all over with “fuck fuck fuck fuck” (Picton, New Zealand) and an umbrella’s violent end as a heap of junk is shown to fortuitously formally mimic the wall graffiti behind it (Amsterdam Impressions Red Light District/ Amsterdam, Netherlands).

“… formal compositions that startle by the power and oddness of their found juxtapositions … which makes a typical Tod Papageorge photograph appear modest by comparison.”

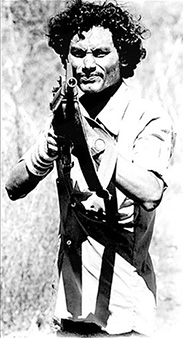

In the final section, Streets in Time, Smith brings together images from various international “pain capitals,” often risking his own neck in the process: El Salvador; Belfast, Northern Ireland; Moscow, Russia; Havana, Cuba; and lastly, Montserrat where Smith was present during several horrifying pyroclastic events near the active volcano there (see Smith’s Molten Memoirs for additional images and text). Here instead of the good ‘n plenty of the streets seen in the scores of images up to this point, we now see a theater of disasters: similar streets but now devoid of people, streets smothered in volcanic ash, or whole areas blown to smithereens as in Plymouth, Montserrat. Smith here also includes gentle portraits of the native inhabitants who, stoically resisting leaving their homeland despite the dangers, seem to say: “These are our streets! And we’ll be damned if we’re going to be driven out.”

Driven on, Smith leaves Montserrat for the States. The book ends on a quirky note concerning consumerism and spectacle that would’ve warmed the heart of Walter Benjamin: a young child imagines playing basketball before a huge upended brand name athletic shoe— a Brobdingnangian replacement for all the shoes Smith has worn out on his global jaunts—its massive rubber sole holding up the basket.

– James R. Hugunin, Chicago, Illinois